As you navigate the octave pedal tone exercises you might start to notice that the octave shapes have a fair amount of predictability, even while the internal sequence of notes differs, sometimes greatly, from one to the next. Becoming familiar with these octave shapes can be very helpful in your playing and understanding of the fingerboard, and can also shine a light on one of the more useful aspects of the CAGED system: the consistency of the octave shapes found within our five open position Major chords.

The most common octave shape is the one found between the outer notes of the 3-string power chords whose bass notes are on the 5th and 6th strings. That’s the octave shape that Wes Montgomery and others most often use to play octave melodies (though for jazzers the D shape octave and upper octave of the G shape also figure in plentifully.)

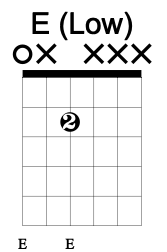

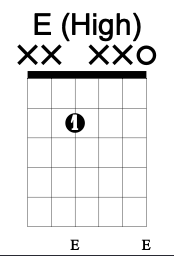

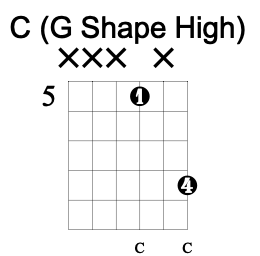

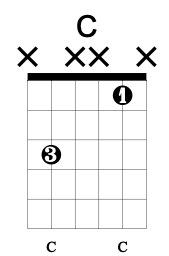

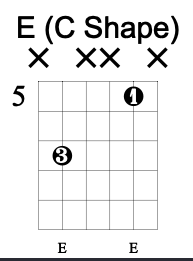

The E chord shape actually has two distinct octave shapes within it: the low one is the box-shape commonly associated with the aforementioned power chords, i.e. “two frets up and two strings higher” while the shape of the E chord’s upper octave is a little more shy about presenting itself. It is the larger upside down L shape that is found between the 2nd fret of the 4th string and the open 1st string. If we move it up one fret we see that it outlines the ‘beginner’ 4-string F chord and, moving onward up the neck, has a shape that can be described as “2 frets down and 3 strings up”. That inverted ‘L’ shape can also be found in the C chord where the octave is found between the 3rd fret of the 5th string and the 1st fret of the 2nd string. It’s the identical “2 frets down and 3 strings up” shape of the upper octave in the E shape.

in the open E Chord

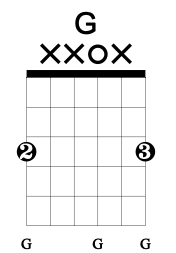

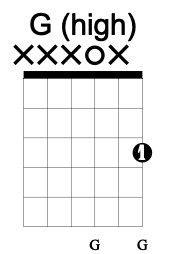

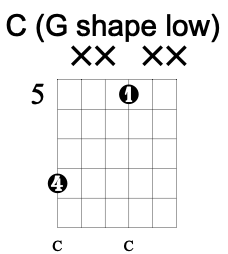

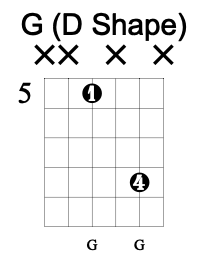

moving to the G shape we have another open chord that contains two octave shapes. This chord’s lower octave is found between the 3rd fret of the 6th string and the open 3rd string. We could say, “3 frets down and 3 strings up”. So, for example, if we looked for the C octave using the lower octave shape of the G chord we would first want to locate the C note at the 8th fret of the low E string and then connect this with the 5th fret of the 3rd string; that follows the 3 frets down and 3 strings up pattern. This shape is a very important one for the octave pedal tone exercise and is a great one to be familiar with because of the amount of space between the octave for melodies and harmonies to be explored!

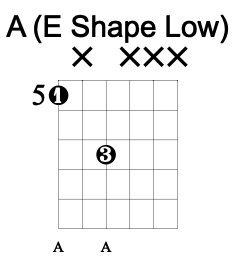

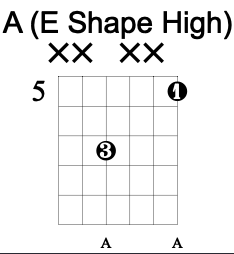

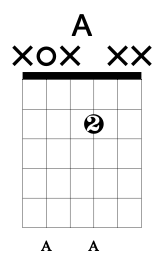

The octave shape found within the A chord shape is identical to the lower octave of the E chord. It is the ‘box’ shape that I earlier described as two frets up and two strings higher.

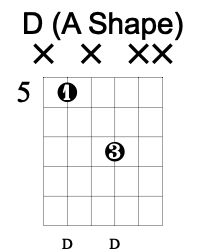

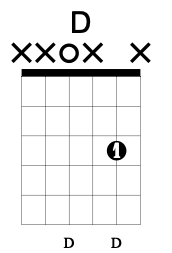

The D chord’s octave shape is found between the open 4th string and the 3rd fret of the 2nd string and as such is identical to the upper octave of the G chord shape.

My personal favourite of all the open chord octave shapes is the C chord! It fits beautifully in the hand and offers loads of melodic and harmonic opportunity in between the low and high notes. The M7 is within easy reach with the 4th finger, the b3 to 3 ornament is a simple 1st to 2nd finger hammer on. There are many beautiful colours readily available and with practice you will see them all, no pun intended: )

So, looking at the 5 chords of the CAGED system, we find 7 octave shapes: 5 chords plus 2 extras in the G and E shapes. Of those 7 shapes only 4 of them are unique/non-redundant. E and A share a shape; C and E share a shape; D and G share a shape and the one shape that doesn’t share itself with other chords is the lower octave shape of the G chord.

Here is a pdf of all the above shapes in one handy place.

Though I may be belabouring the point a little, the important thing to know is that getting really comfortable with your octave shapes is a great way to bolster your conception and understanding of the harmonic and melodic layout of your fingerboard.

Thanks for visiting and Happy Practicing!